Three months into a predictive maintenance project, your model starts producing false positives. The accelerometer data looks fine. The temperature logs look fine. But the model triggers alerts on normal equipment.

The problem: your accelerometer samples at 1kHz, your temperature sensor at 0.1Hz, and somewhere in your pipeline, a script interpolated temperature values using future readings. The model learned a correlation that doesn’t exist in real-time operation.

This isn’t a modeling failure. It’s a harmonization failure.

Modern ML systems pull from sensors, logs, simulations, and control systems, each with its own sampling rate, noise profile, and failure mode. Bringing these sources together is often called “preprocessing.” What you need is data harmonization: the process of unifying disparate data sources into a consistent format that preserves meaning across modalities.

This article explains what harmonization means for multimodal time-series, why ad hoc preprocessing fails, and why harmonization must be treated as a system.

From Preprocessing to Harmonization

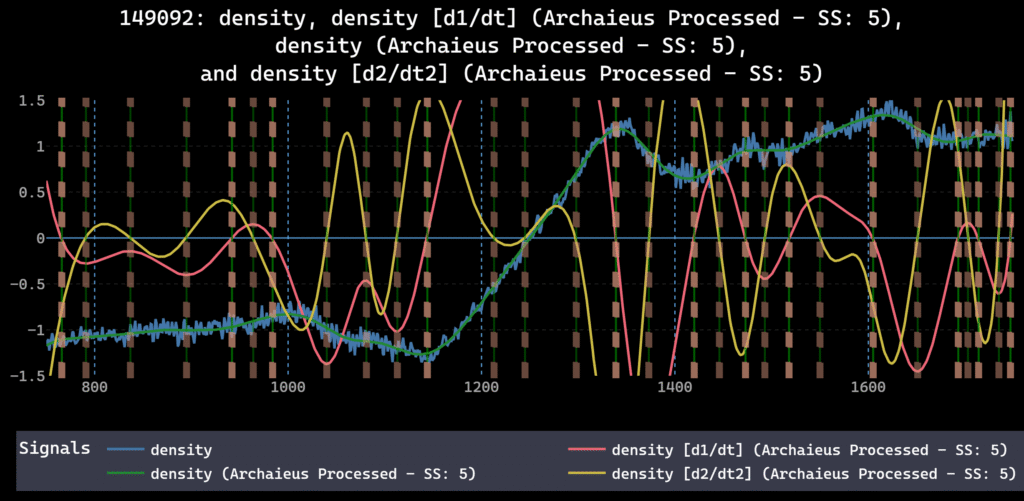

In the previous article, we explored why preprocessing order of operations matters. The key point: preprocessing steps aren’t interchangeable, and order-sensitive operations reshape the meaning of data in ways that break models.

Harmonization follows from that.

If preprocessing asks, “How should this signal be transformed?”, harmonization asks: “How do these signals relate to one another, and under what assumptions can they be combined?”

The Multimodal Reality

Most real-world systems generate data through multiple channels:

- Continuous sensor measurements sampled at different rates

- Event-driven logs that update irregularly

- Derived features computed on sliding windows

- Simulation outputs generated on their own grids

Each source may be internally coherent but incompatible with the others. They don’t share a common notion of time, scale, or meaning. A 2025 survey on multimodal time series analysis identifies data heterogeneity, modality gaps, and misalignment as the primary barriers to effective analysis.

Harmonization creates that shared reference.

Many preprdynamics.

Common Harmonization Failures

These errors appear constantly in multimodal pipelines:

- Using future data during alignment. Interpolating with bidirectional methods leaks future information into past observations.

- Normalizing before alignment. Scaling signals before they share a common temporal reference distorts relationships between sources.

- Ignoring sampling rate differences. Treating signals with different frequencies as synchronized creates phantom correlations.

- Assuming timestamps are accurate. Sensor clocks drift. Network latency varies. Two signals timestamped identically may represent different moments.

- Undocumented order of operations. When scripts are added incrementally, the sequence of transformations becomes implicit and irreproducible.

Each produces pipelines that work on development data but fail in production.

Why Ad Hoc Preprocessing Breaks Down

A common approach is incremental: a new signal is added, a quick script aligns timestamps, another rescales values, another fills gaps.

This works initially. Over time, failure modes emerge.

Assumptions accumulate silently. One script assumes forward-filling is acceptable. Another assumes interpolation is safe. A third normalizes using statistics computed over the full dataset, including future data.

The pipeline becomes order-dependent in undocumented ways. Reproducibility erodes. When results change, it’s difficult to determine whether the cause was the data, the model, or preprocessing logic scattered across scripts.

These issues are the natural outcome of treating harmonization as an implementation detail.

Harmonization as a System

To harmonize multimodal data reliably, several questions must be answered explicitly:

- What is the common temporal reference?

- How are gaps handled, and under what causal assumptions?

- Which operations mix information across sources?

- How are differences in scale and units reconciled?

You can’t answer these one script at a time. A harmonization system defines:

- A consistent order of operations

- Clear boundaries between stages

- Explicit assumptions about causality and alignment

- A record of how data was transformed

Without this structure, pipelines break silently.

Alignment Is the Foundation

The most fundamental step is temporal alignment. Alignment establishes a shared notion of time across signals. Without it, comparisons are ambiguous and causal reasoning breaks down.

Matching timestamps isn’t enough. Alignment involves understanding delays, latencies, and sampling jitter. A Scientific Reports study notes that sensor calibration, time synchronization, and data alignment are prerequisites for any downstream fusion.

Common techniques include timestamp normalization, dynamic time warping (DTW), Kalman smoothing, and sliding window methods.

Because later operations assume alignment is correct, errors here propagate forward. Alignment should happen early and consistently.

Filling, Resampling, and Causality

Time-series data is rarely complete. Sensors drop out. Logs skip intervals. Filling and resampling are necessary, but they come with assumptions:

- Does filling use future information or only past data?

- Does resampling preserve energy, averages, or peaks?

- Does smoothing alter phase relationships?

Each choice affects how signals relate to one another. In a harmonized system, these decisions are explicit. The same causal constraints from preprocessing pipeline order apply: operations that blend past and future create shortcuts that don’t exist at inference time.