Your anomaly detection model worked in testing. In production, it misses half the faults. Three engineers labeled the training data over six months, each using different criteria for “abnormal.” One labeled onset. Another labeled peak. A third labeled the entire window.

The model learned an average of three definitions. It predicts none of them reliably.

This isn’t a model problem. It’s a labeling problem.

For images, labeling is straightforward—objects are static, labels are discrete, context fits in a frame. Time-series works differently. Events unfold over time. Boundaries are ambiguous. Context spans multiple channels. This article explains why labeling time-series data differs, where pipelines fail, and why reproducibility matters.

Why Time-Series Labeling Differs from Image Labeling

In image classification, a label answers: what is this? The object exists all at once. The label applies to a static input.

Time-series labeling answers: what is happening, when does it start, and when does it end?

Labels are temporal—they have duration, not identity alone. Events may overlap, evolve gradually, or lack sharp boundaries. The meaning of an event often depends on context not present in a single signal.

Labeling time-series data requires interpretation.

The Boundary Problem

One of the most persistent challenges is defining event boundaries:

- When does an event begin?

- When does it end?

- What happens during transitions?

Different labelers, even domain experts, disagree, especially for events that emerge gradually or decay slowly. These disagreements reflect genuine ambiguity in the data.

Many labeling pipelines assume boundaries are precise and objective. Models trained on such labels inherit this assumption, leading to brittle behavior near transitions and poor generalization.

Boundary ambiguity isn’t a failure, but rather a property of temporal data.

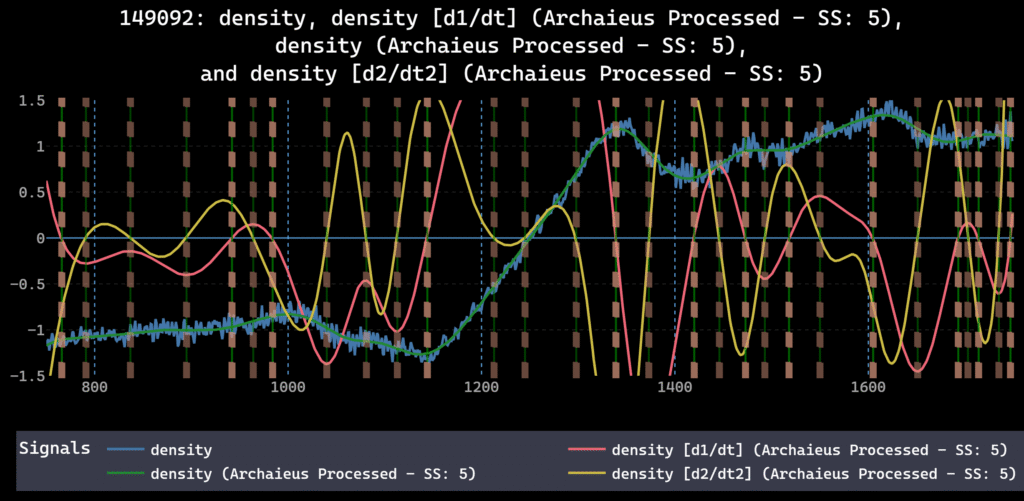

Context Spans Multiple Signals

A single measurement rarely carries enough information to determine a label. The same value means different things depending on what came before, what comes after, and what other signals show at the same time.

Labels are contextual, not local.

Pipelines that label signals independently, one channel at a time, one window at a time, miss this. They produce labels that are internally consistent but globally incoherent.

Effective labeling requires synchronized, harmonized views of multiple signals over time.

Common Labeling Pipeline Failures

These failures appear constantly in production:

- Preprocessing changes, labels don’t. Signals are resampled or filtered, but labels reference the old data structure.

- Thresholds stay fixed while signals drift. Automated labels become misaligned with the underlying phenomenon.

- Labeling criteria aren’t documented. Different annotators apply different definitions over time.

- Labels aren’t versioned. Models trained on different label sets can’t be compared.

- Corrections aren’t propagated. Fixes applied in one context don’t reach downstream datasets.

These failures show up as gradual performance degradation, unexplained inconsistencies, or models that “mostly work” but can’t be trusted.

Manual, Automated, and Hybrid Labeling

Manual labeling remains the gold standard. Human experts integrate context, apply judgment, and recognize subtle patterns.

But manual labeling doesn’t scale. It’s time-consuming, expensive, and hard to reproduce. Different experts apply slightly different criteria. Standards drift.

Automated labeling, using thresholds, heuristics, or model-based approaches, offers speed and consistency.

But automation encodes assumptions in code, often invisibly. Small changes in preprocessing or noise levels shift labels unexpectedly. Automated labels appear objective, making them easy to trust even when wrong.

Hybrid approaches combine both: automated labeling with manual review, or manual labels used to tune detectors. This is often the right direction, but raises new questions:

- Which labels are authoritative when disagreements arise?

- How are corrections propagated?

- How do updates affect downstream datasets?

Without explicit structure, hybrid pipelines become inconsistent.

Why Provenance Matters

Provenance answers questions that labeling pipelines must handle:

- What data was labeled?

- How was it preprocessed?

- Which algorithm or criteria produced the label?

- With what parameters?

- At what time, and under which assumptions?

Without this information, labels become disconnected from their origins. They’re static artifacts rather than interpretable decisions.

In time-series workflows, where labels depend on context and preprocessing order, this disconnect breaks debugging and reproduction.

Labels Shape the Entire Pipeline

Labels influence:

- Feature extraction

- Model architecture choices

- Evaluation metrics

- Deployment behavior

If labels are inconsistent, unstable, or poorly documented, the entire pipeline inherits those flaws.

Best Practices for Time-Series Labeling

- Document labeling criteria explicitly. Write down what counts as an event, where boundaries are drawn, and how edge cases are handled.

- Version your labels. Track which labels were used for which experiments. Treat labels as data, not constants.

- Align labels with preprocessing. When signals are resampled or filtered, regenerate or validate labels against the new structure.

- Use causal context only. Annotators should see only past and present data when labeling, not future context unavailable at inference time (e.g., when forecasting)

- Track provenance. Record who labeled what, when, using which criteria and parameters.

- Validate automated labels. Spot-check against manual annotations. Monitor for drift as signals change.

Scaling labeling requires consistent harmonization, explicit logic, versioned assumptions, and traceable lineage from raw signal to final label.

What Comes Next

Labeling is where many ML pipelines break, not because labeling is hard, but because it’s treated as simpler than it is.

Time-series data demands a different approach. Labels are temporal, contextual, and assumption-laden. They must be created, reviewed, and revised within a framework that makes those assumptions explicit.

Recognizing labeling as a first-class problem follows from understanding preprocessing order and harmonization. For teams evaluating tooling, our overview of labeling platforms covers where existing solutions succeed and where gaps remain.